I visited Cuba during a tender moment of its life: in the past year, various U.S. travel and financial restrictions have been lifted, however the status of its long-standing embargo is still up for debate. With the thawing of this previously hostile relationship also comes an influx of tourism, both American and from those who want to visit before the Americans flood in. Even so, tourism is still moderate enough that the country has not yet succumbed to its cancers (read: multinational corporation takeovers).

Visitors are quick to fawn over Cuba for being a time capsule. The colorful old-school automobiles, the ornate yet decaying Spanish colonial buildings, and the general lag that results from minimal exposure to the Internet and technology all contribute to the country’s undeniable charm. I felt this juxtaposition of modernity against history straight out of the airport, when I was picked up in a 1954 baby blue Chrysler playing reggae from a bootleg sound system, by a driver who loudly talked in his phablet while manually tying my suitcase to the roof of the car.

I’m personally guilty of gawking at Cuba’s antiquated aesthetic and squealing with glee whenever a candy-colored 1950s car passed by. It didn’t take me long to realize, however, that the country’s suspended state of being is only cute to the outsider. There is far more going on beyond what meets the eye.

GET ACCESS TO MY FREE MASTERCLASS

How to Create an Audience of Highly Engaged Buyers Through Irresistible Storytelling

I was lucky to experience Cuba through the eyes of a local millennial. My Cuban escort, whom I was connected with through a friend of a friend’s friend, was instrumental in helping me see past my rose-colored lenses and into the country’s unfiltered political, economical, and social state. Getting the inside scoop from a local is made purposely difficult, as the country’s laws are set up to limit interaction between foreigners and locals beyond tourist services. But more on that later.

With the assistance of my newfound Cuban friend and others that I made along the way, I learned that Cuba is much more than a time capsule – it is a country still deeply entrenched in a complex political situation, a struggle for financial stability, and teetering on the brink of a collective craving for a better life.

The Current State of Cuban Life

My understanding of Cuba began to take shape once I inquired into the realities of people’s daily lives. I was shocked to learn that Cubans on average earn only $20 a month – that means people work for less than $1 a day. Though this figure is relatively adjusted to the country’s much lower cost of living, it’s still just enough to get by.

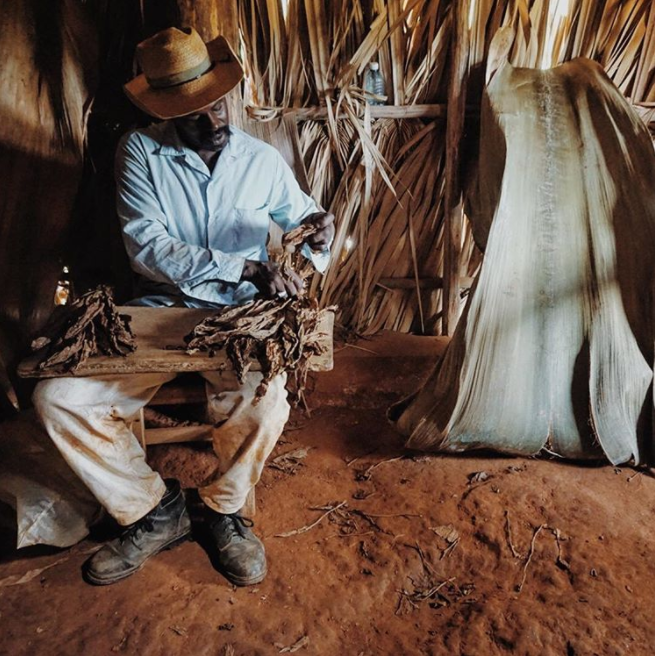

The government heavily relies on its people’s productivity to run the economy, yet appears to give little in return. Cubans are given a piece of land to live on so long as they agree to sell most of whatever they produce on it to the government for a standardized price: at the tobacco farm that I visited, farmers are obligated to sell 90% of their product to the government (for Cuban cigars, which as we know are quite expensive), leaving only 10% of their hard-earned work for personal consumption or significantly more profitable sale. Cubans who do not produce have to pay heavy taxes or get their land taken, and those who want to own private entities are made to pay such hefty fines that their profit is not much better than if they worked with the government.

When it comes to the economy, the state does what it will, and no one is given an explanation as to why. The government placates Cubans by keeping them ignorant to the fact that life could be any other way. While I first found it charming that some locals have never heard of the name McDonald’s or Starbucks, it later struck me as a blatant sign of how little they know about the world outside of their country. The history they study is their own, the story they’re told is biased to favor the government, and their contact with tourists is monitored and in some cases, punishable by law. My Cuban friends were stopped by the police and questioned on their involvement with me every time we drove somewhere, only to be warded off by bribes (apparently, the police is financially motivated to give inhabitants fines as it boosts their own salary at the end of the month). Despite questioning them for half an hour each time, the police never bothered me personally.

Everywhere I went, I was taught that Cuba’s Revolution of 1953-59 was a response to “Yankee imperialism” and the resulting unjust divide between the rich and the poor. Ironically, it seems that communism has displaced, rather than closed, this gap. I was surprised to learn that the country operates on two currencies: the Cuban peso (CUP, otherwise known as the national coin), and the convertible peso (CUC), which is equivalent to 25 CUP and en par with the U.S.’s dollar value. Aside from being incredibly confusing, the double currency situation plays a key role in socioeconomically separating locals from visitors.

High-quality consumer goods and tourist services are priced at foreigner-adjusted CUC, meaning that most locals cannot afford them. For example, killing cows for red meat or independently selling fish is illegal, meaning legally consuming either costs a fortune. Conversely, the very cheap and lower-quality goods such as household items and food staples that can be purchased with CUP (the national coin) are issued by the government and made largely inaccessible to tourists. This creates two parallel markets: an expensive, high-quality one reserved for foreigners and the selective wealthy (mostly high-ranking government officials), and a lower-quality, affordable one for locals. It’s no wonder that there is a third, booming black market for expensive and prohibited goods.

“El Cubano Inventa Mucho“

I was blown away by Cuba’s beauty and charm, but I was even more impressed with Cubans’ resourcefulness when it comes to circumventing the unfair living conditions bestowed upon them.

What became very clear, very quickly, is that the average Cuban cannot survive by playing by the government’s rules. Cubans are often left with little choice but to take back from the government – primarily through the black market – because they simply do not make enough money to live comfortably otherwise.

I jokingly commented to a group of young Cubans that their economic situation reminded me of The Sims, a life simulation video game I played as a child: the characters you create start off with no money; to get a better job, they need to build certain skills, but to acquire those skills, they need money to buy resources. The only way to really break the cycle and significantly improve their lives is to hack the system with a cheat code that gives them the extra money they need. As if on cue, they solemnly nodded in agreement; they could not believe that this was a game for Americans, when for them it was an everyday reality.

Rather than succumb to a system designed to work against them, Cubans have innovatively found ways to hack it. This is an interesting contrast from the U.S.: while the entrepreneurial spirit in America is celebrated, in Cuba it’s almost a necessity. As a Cuban millennial who I spoke with said, “el cubano inventa mucho” (the Cuban invents a lot). There is an entire underground market built to counterbalance the government’s stifling restrictions, allowing them to purchase the red meat and fish they can’t otherwise afford, access flash drives filled with popular U.S. TV shows to compensate for their five biased national channels, and exchange foreign cash without having to pay the bank’s ridiculous transaction fees. Those who know how to successfully navigate the black market, succeed in maximizing the quality of their daily life.

When I asked my Cuban friend why he wanted to leave the country, he answered with two simple words: “Para mejorar” (to improve). Frustration was a recurring emotion that emerged while speaking to locals, especially amongst the younger generation. Despite the knowledge gaps, Cubans are not naïve. They realize that they’re cut off from the rest of the world and that their existing knowledge is limited by what the government permits. I found in them a genuine desire for a better life, without having a clue as to how that could manifest due to their deprived access to information.

As we sat on a hilltop overlooking Havana’s illuminated skyline and sharing a bottle of Havana Club, one of my new friends commented that communism in Cuba was created to be accepted but not understood. Again, I was taken aback by their acute awareness of the political situation and the world that exists beyond their confines. It hit me then that it’s a very real possibility that the majority of Cubans today do not aspire to the philosophy the country was built around post-Revolution – that they just follow it because it’s the life they’ve been dealt. Communism on paper is indeed a beautiful notion; it is in practice that it becomes easily corrupted.

Happiness Is Up To The People

Although I personally do not endorse communism, I did a find a silver lining in its role in Cuba. For communism to work, its participants must inherently cultivate a strong sense of community. One of the first things I noticed traveling through the country was how much Cubans look out for one another and make the best of what they have. Cubans are some of the kindest, warmest, and overwhelmingly appreciative people I’ve met traveling, especially when it comes to welcoming visitors. I’ve never felt so genuinely wanted as a tourist in another country.

Their general happiness and resourcefulness is a reflection of the solidarity they’ve built by creating an extensive support network. People share things with each other because they want to and because it collectively makes everyone’s lives easier: from T.V. show flash drives, to parts for their consistently deteriorating cars, to rides to and from the city. Their sense of community is palpable and what I believe inherently keeps them happy despite circumstance.

At the end of the day, the fact that the country severely lacked amenities and everyday comforts (I’ve developed a newfound appreciation for toilet paper and running water) didn’t matter to me. All I felt as I was leaving Cuba was joy.

Cuba taught me that creating collective happiness goes far beyond money, politics, or consumerism. It is about cultivating a sense of community. The ability to rely on your fellow humans and know that someone has always got your back is precious.

When we strip away all the distractions that occupy our attention during our daily lives – the main culprits being technology, advertising, and materialism – all that is left is people. This is what Cuba’s soul is composed of, and why they are more than happy spending their days dancing to live music, socializing with one another, meeting in public spaces, and having face-to-face conversations. Without our fancy gadgets, we get to focus on what is priceless: human connection.

Want to become the best story

YOU'VE EVER TOLD?

Get behind-the-scenes weekly insights from me on all things storytelling,

branding, conscious life design, and other fun surprises!